Huehnergard’s Grammar of Akkadian, Lesson Two

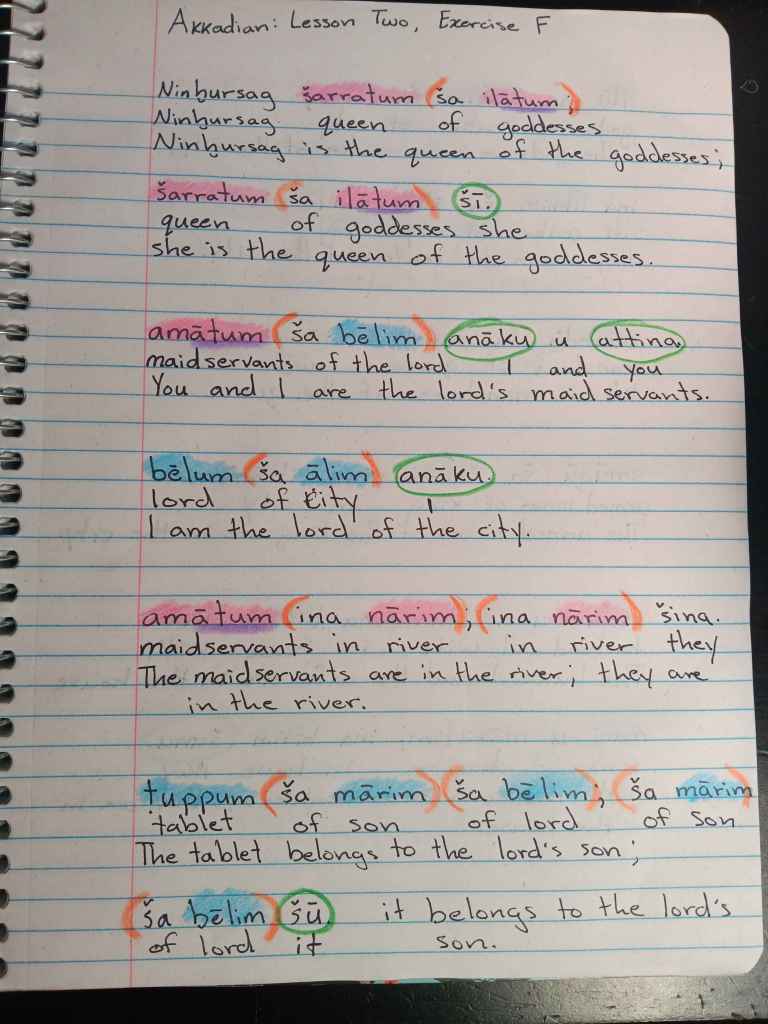

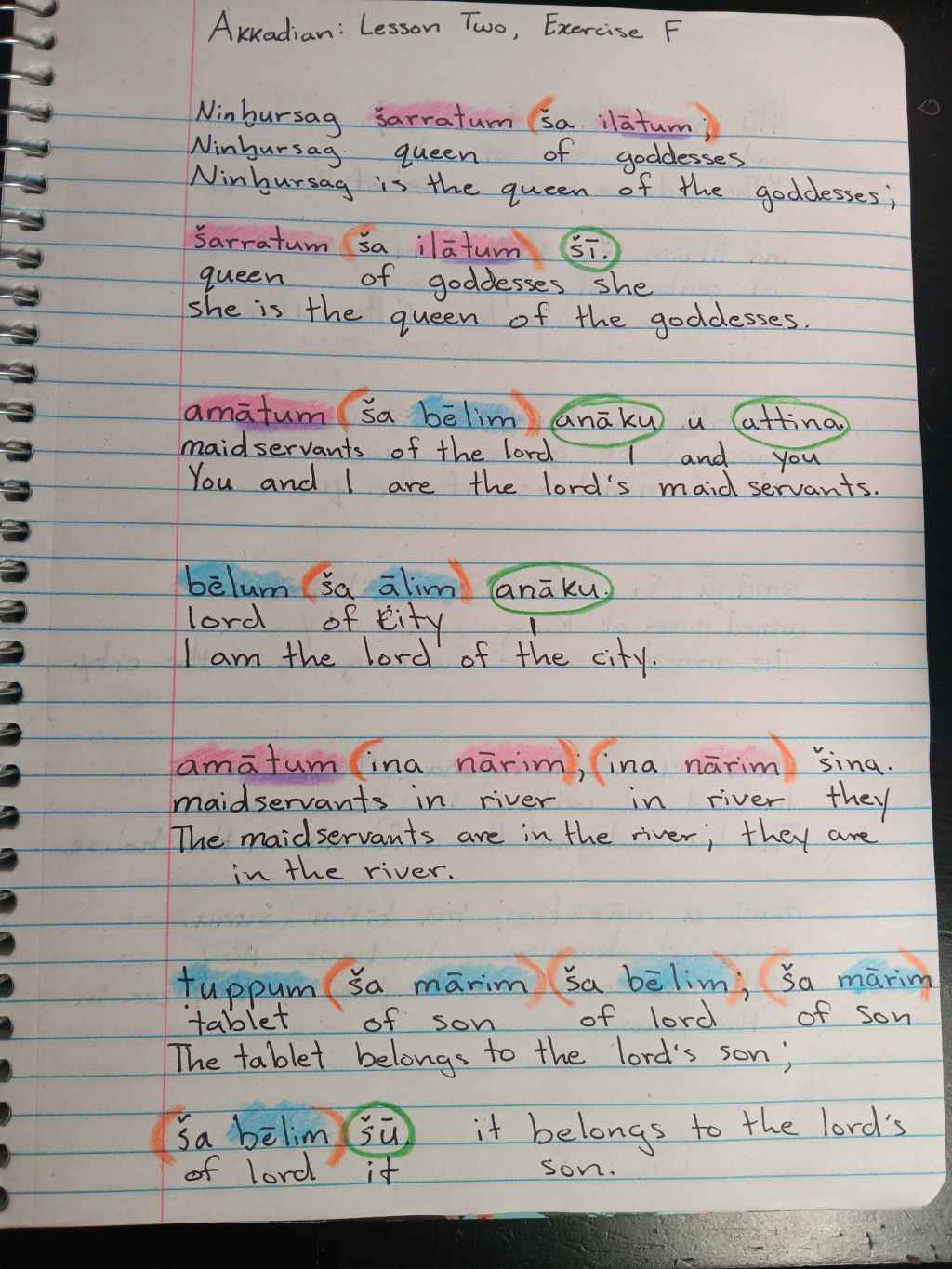

This week I was seeing if I could figure out some sort of color coding to help with translation exercises. It’s still a work in progress to see what works best, but here’s an example from the Akkadian to English translation exercises.

The idea was to distinguish gender (pink vs. blue), case (using the orange parenthesis to indicate a prepositional phrase) and number (underlining the plural indicator). And then I just circled the pronouns.

I translated the sentences word for word on the second line, and then did a proper translation as my final answer on the third line.

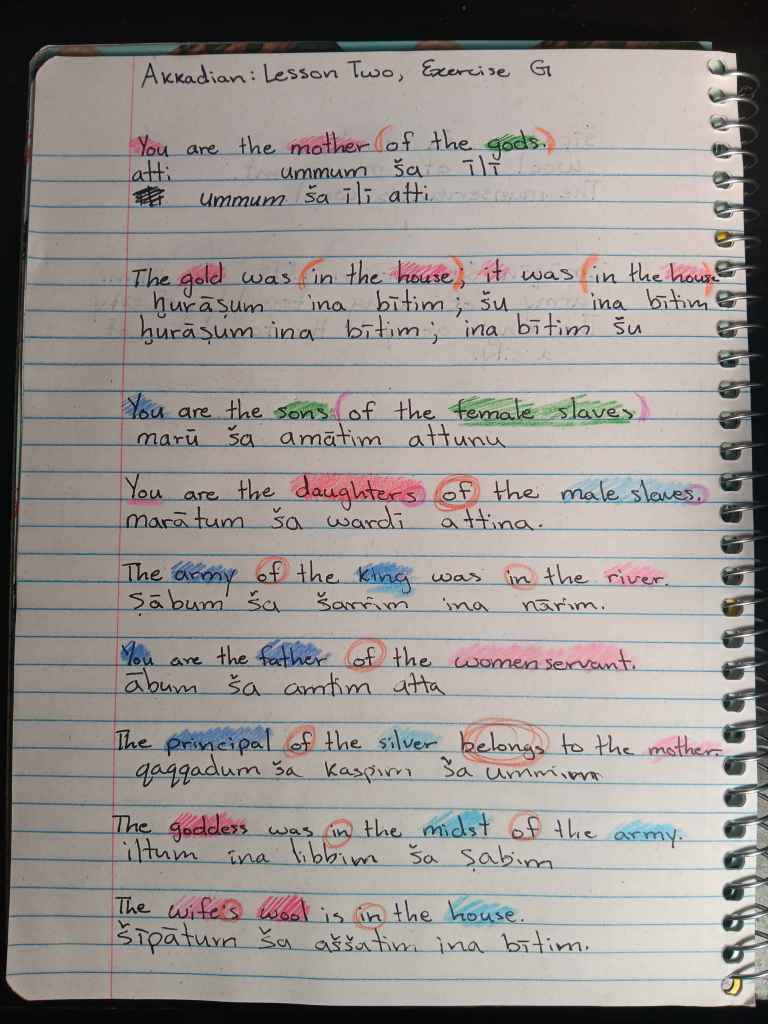

On the other hand, my English to Akkadian color coding was much more chaotic and experimental. 🙂

There is no set rule I have so far, and in pretty much each sentence I was trying out something different. My main focus was marking the words that would be translated (Akkadian doesn’t have the articles “a” and “the” and doesn’t use the verb “to be” so I didn’t have to worry about those words). But trying to mark gender didn’t make much sense, because those words don’t carry a gender in English, and trying to convey case and number via color code has not yet been successful.

Gender, Number, and Case

In other news, after reviewing this lesson closer, I found an answer to my question from last week. I was confused that if bītum and liptum are masculine nouns, then why are they feminine in the plural?

Apparently this is a feature of Akkadian grammar, as it is stated in Lesson Two ” Many nouns that are masculine in the singular are always or sometimes construed as feminine in the plural” whereas “All nouns that are feminine in the singular … remain grammatically feminine in the plural.”

A common concept for many languages, grammatical gender is something rather abstract but incredibly interesting. English lacks it for the most part, although it existed in Old English, and we still retain gendered pronouns (he/she/it), but we lack the surrounding structure in our language that inflected languages like German, French, Russian, or Latin have. Colloquially we might assign gender to inanimate objects, a ship or a car is often a “she,” for example. But this is not a grammatical rule.

Around the time when Old English became Middle English is about when it dropped its grammatical gender. The dividing line between the two is generally considered to be in AD 1066, the Norman Conquest. Prior to that the Anglo-Saxons spoke what we now call Old English, and afterwards, with the influx of external influence, English morphed into its Middle English age, and along the way, tossed out its gendered nouns.

“Grammatical Gender — a grammatical category in inflected languages governing the agreement between nouns and pronouns and adjectives” The Free Dictionary by Farlex

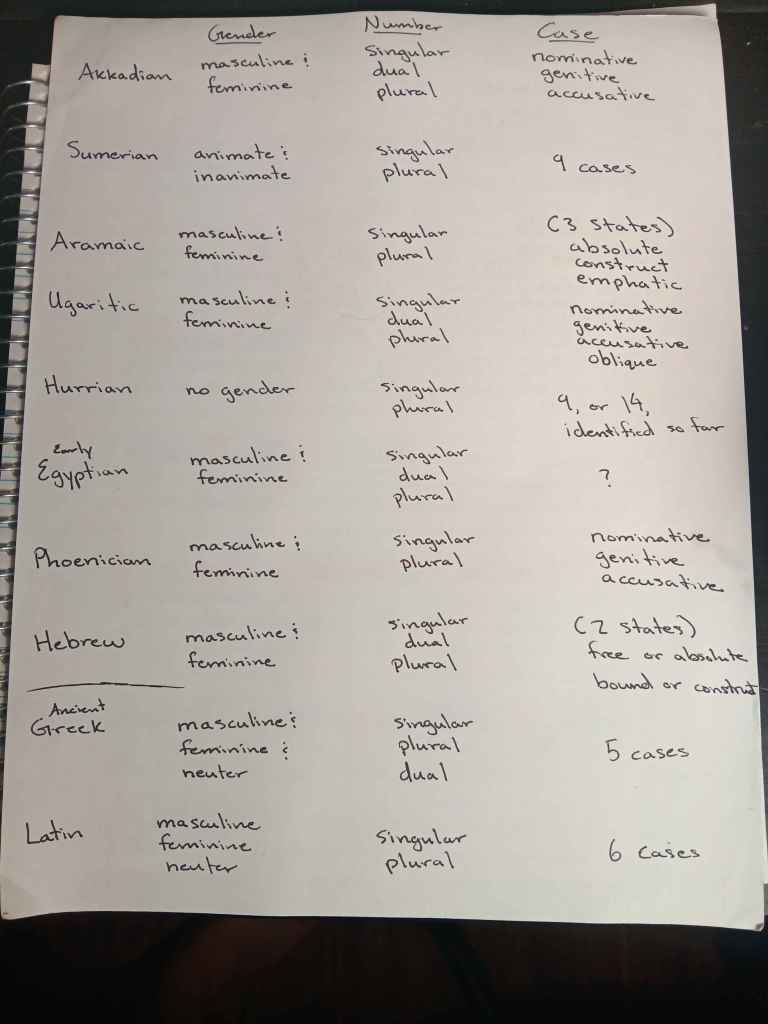

Out of curiosity I wanted to compare neighboring and related languages, so I drew up a chart using the Cambridge Encyclopedia of Ancient Languages as source material. I included Greek and Latin at the bottom for a sort of familiar basis, as most of us generally have more context for those languages than any of the others mentioned.

The most interesting difference in the gender column, is Sumerian distinguishing between animate and inanimate rather than masculine and feminine. Elamite also does this, though I didn’t include that language in this chart. Animate refers to people and divine beings, and inanimate is everything else, including animals.

I also noticed that, unlike in Greek and Latin, neuter nouns don’t appear to be a thing in ancient Mesopotamia.

In the number column, the only distinction was whether or not a language used a dual form. Which languages did and which didn’t was pretty evenly spread between the ones I was comparing. It also sounded like, when I was reading the overviews for these languages, it was not uncommon for a language to have a dual form at one point only for it to fall out of use in later generations.

The concept of number is pretty straight forward, there are singular nouns (cat, tree, person) and plural nouns (cats, trees, people). Dual nouns are something that English doesn’t have, and they specifically refer to groups of two. While I can’t speak for the other languages listed, Akkadian’s usage of the dual form is generally only for natural pairs. “My eyes” is, as the example given in Lesson Two, literally translated from Akkadian “my two eyes.” Legs, arms, ears would also use the dual form.

Case is quite a bit more variable between these languages. Aramaic and Hebrew are interesting in that their nouns are distinguished by states instead of grammatical cases. Hurrian looks like fun with 9, or 14, depending on how a case is defined, and that’s what’s been identified so far.

Unfortunately, I could not get much information on Egyptian nouns as the article was very broad and covered Early, Middle, and Late Egyptian and also Coptic, which spans a lot of centuries and a lot of grammatical changes. The only section I came across discussing nouns just said that Early Egyptian had masculine and feminine nouns, and then went to discuss other things. There was, however, a very detailed and interesting chart of the Egyptian hieroglyphs that distracted me from my purpose for a while. 🙂

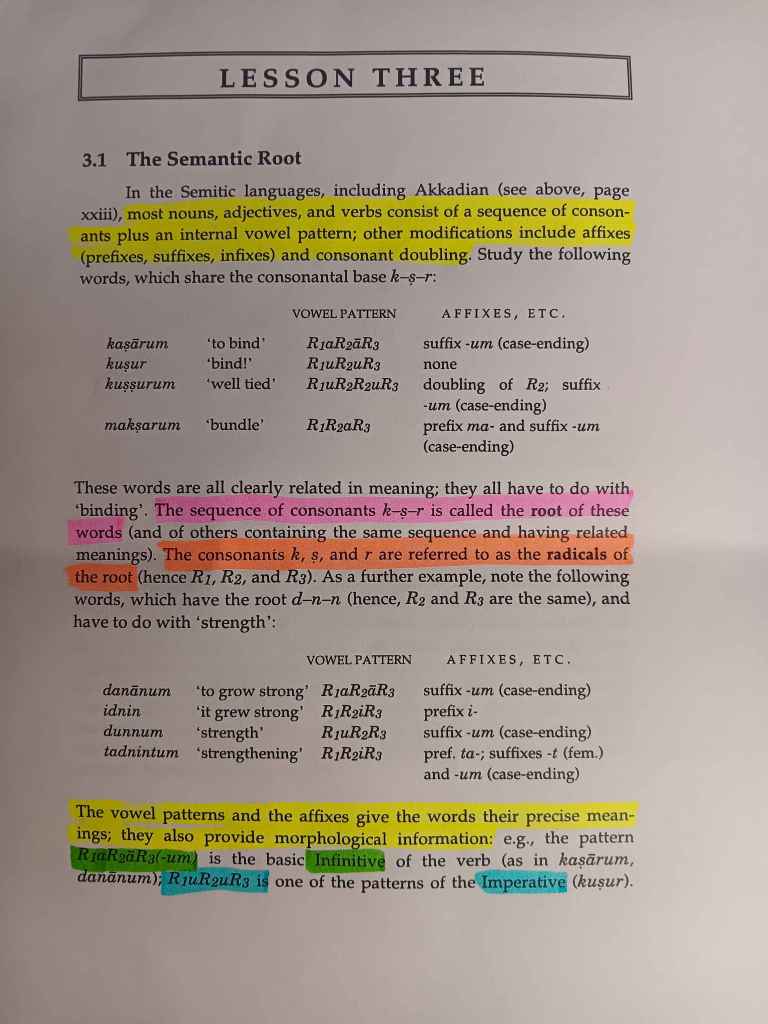

Cuneiform

I cannot believe I was going to try to bypass learning cuneiform with clay. This has been so much fun to practice. For a stylus I’m just using a popsicle stick with the rounded end cut off, and the clay is just Plastilina modeling clay, it says it never dries, but I still keep it in a plastic bag when I’m not using it, if only to keep it from getting dirty.

The first picture is the symbol for “king” which I did a few times, and the second picture is the first seven symbols of the Ugaritic alphabet, each reiterated a few times as well. Even though it’s not specifically Akkadian, I still feel like it’s good practice to get used to writing cuneiform, and the diagram in Huehnergard’s Intro to Ugaritic has been very helpful.

This week took a little bit longer than a week. And next week looks to be getting a step more technical in grammar, so I’ve finally gotten my highlighters out. 🙂

Leave a comment